How Ms. Magazine Started a Revolution—and Why It’s Far From Over

Image: Courtesy of HBO

The directors of the new HBO documentary Dear Ms.: A Revolution in Print talk about the magazine’s storied history and why its “consciousness-raising” is needed now—more than ever.

“Try to imagine a life where you are owned by or controlled by the men in your life.”

This opening line of the documentary Dear Ms. pulls viewers into a past reality that, for many women, isn’t so hard to imagine today. Rights we thought were assured—control over our bodies, our money, our choices—once again feel as flimsy as a page torn from a magazine.

While 64 percent of Americans see feminism as empowering, nearly half also call it polarizing, and a third consider it outdated, according to Pew Research. So how did we get from Ms. to this, and what does the turbulent, radical story of the magazine reveal about the unfinished work of feminism now?

Inside the Ms. Documentary

The story of Ms. is told through the eyes of three directors: Salima Koroma, Alice Gu, and Cecilia Aldarondo. They each bring a different lens to this history, starting from iconic covers of the magazine and delving into the complicated backstory of the fledgling feminist movement and its new mouthpiece.

“We’re a movement, which means we’re messy, which means we disagree, which means we need to have hard discussions,” Aldarondo said. The documentary captures those tensions and contradictions, portraying Ms. not as a perfect movement, but as a living, evolving experiment in consciousness-raising. One that’s still unfolding in today’s fights over whose voices get heard, what feminism means, and who it’s for.

Salima Koroma, Alice Gu, and Cecilia Aldarondo – Jamie McCarthy/Getty

‘Feminism is a Dirty Word’

Koroma recalled telling Ms. co-founder Gloria Steinem that people her age see feminism “as a dirty word.” The legend’s response? “It’s always been a dirty word.”

“I don’t know if we necessarily anticipated or even made this film expecting for women’s rights to be so threatened,” Aldarondo admitted. Gu agreed: “It’s easy to go through life like, I can drive a car, I have a bank account, my husband doesn’t beat me, and he wouldn’t even dream of it, thank God, I can wear pants. Look, the three of us … we’re all directors, we’re all women of color … We’ve come a long way, but … there’s still many, many areas where we have a long way to go.”

The Origin Story

Some of the other names originally considered for the magazine may sound more extreme today, like Sojourner, Lilith, Bimbo, or Bitch. But “Ms.”—combining Mrs. and Miss—represented a revolutionary new status of marital and professional independence for women in the 1970s. And men weren’t quite ready for it: ABC News Anchor Harry Reasoner gave the magazine six months. Then the debut edition sold out—and Reasoner had to apologize on air.

There was a hungry market for topics like “De-sexing the English language” and “How to write your own marriage contract.” The inaugural edition splashed the shocker “We have had abortions” across two pages. More than 50 women signed their names—including many well-known public figures. Some hadn’t even had abortions. They signed in solidarity, risking legal action.

Breaking Taboos

“I think we were smarter than we thought we were,” Steinem says in the film of those early days. “A lot of these articles could still be relevant.” Decades before #MeToo, the magazine shone a light on dark realities, opening conversations on previously taboo topics. Ms. was the first women’s magazine to cover domestic violence in 1976 and the first national publication to feature sexual harassment on its cover in 1977.

Why did it take a magazine to legitimize what women had long been screaming into the void? “It wasn’t something that was really talked about,” Gu noted, telling the story of a friend who recently admitted she’d been the victim of spousal abuse for a decade. “She’s a complete feminist. She’s very strong, she’s very vocal. So, it still happens. And a lot of these were secrets … I think it’s still hard to talk about.”

Consciousness-Raising Group

Ms. stepped into the public sphere as a kind of “virtual consciousness-raising group,” Aldarondo underscored. “It was a way for women who were isolated, who didn’t have people around them to be able to go, ‘Hey, let’s go to this meeting.’ You have your magazine every month, and that’s your meeting.”

Koroma pointed to the piles of letters Ms. received from women all over the country that affirmed this community—and gave the film its Dear Ms. title. “It’s a lot of women who are reading these things and saying, ‘Oh, that’s my experience too.’ And then they’re writing in and they’re connecting in that way as well. So I think also the letters were a place for this forum, this consciousness-raising group where women could express their experience.”

Image: Jill Freedman/HBO

Race and Representation

Ms. intended to speak for all women, but it faced critiques early on about its editorial whiteness. Still, when it finally put a Black woman on its cover in 1973, it risked losing some readers in the South. Ms. recruited novelist Alice Walker and Essence editor Marcia Ann Gillespie to expand the conversation, bringing in new voices and helping explain how Black women’s issues were unique to them.

That conversation continues today. “As a Black woman, I think of feminism very intersectionally,” Koroma reflected. “I think of class, race, racism. And I think traditional feminism has missed some people … I hear the critiques, and I agree with the critiques. And I also know as an intersectional feminist, I know what the feminists of the past were able to do, and where they also missed the mark for me.”

Pop Culture Machismo

Ms. was also challenging popularly accepted notions of gender. In one memorable montage, the film shows a series of overtly sexist clips from some of the most popular family TV shows of the 1970s. “Young women now, they may think that it’s an outdated thing, it doesn’t matter anymore,” Gu said of the feminist movement. But those shows, which reflected the larger culture, “are not that long ago.”

The editors wanted to liberate men from those gendered social constraints as well, publishing a controversial “Men’s Issue” in 1975. Then-superstar Alan Alda, of M*A*S*H fame, coined the pre-toxic masculinity term “testosterone poisoning” on the pages of Ms.—and took the heat, dubbed a “wimp” for his feminism.

The Porn Wars and Feminist Disagreement

Ms. also covered previously taboo subjects like female masturbation, orgasms, and genitals. It was pro-sex, pro-erotica, and pro-pleasure—but not pro-pornography, which its editors considered to be created by and for the male gaze. Women who asserted porn was self-expression, not exploitation, protested outside the Ms. offices.

Aldarondo sees a missed opportunity in bringing those voices into the conversation sooner. “The questions that they’re raising of what would it be like if we could actually create ethical, diverse, beautiful, women-centered pornography that centers our experiences … they’re still very much in the margin.” She draws lessons from the “porn wars” for other “sticky issues” of feminism today, like making space in the movement for trans women. “Who are we not listening to?”

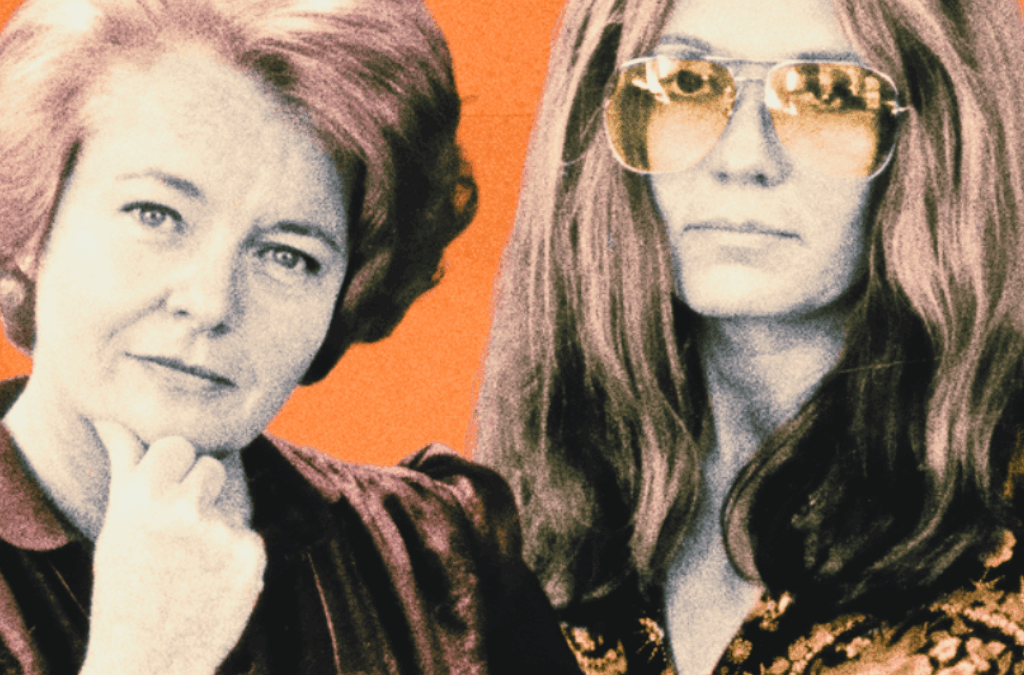

Patricia Carbine, Gloria Steinem – Bettman/Getty

More Than a Magazine—Still a Movement

Try as it might, Ms. could never speak for all women—or men—at once. But raising the collective consciousness was always more important than speaking as a monolith, as Koroma, Gu, and Aldarondo make clear through their film.

“Even though, yes, we talk about the mistakes made, Ms. was extremely brave in saying, ‘We don’t want everybody to agree, we’re going to publish a variety of opinions’—you know, they got tons of backlash,” Aldarondo said. “That’s something that I think is to the credit of Ms.” The msmagazine.com motto today? “More than a magazine, a movement.”

What Now?

“I love the idea of reintroducing and destigmatizing feminism for a younger generation,” Aldarondo said. “I think we need to bring back the consciousness-raising groups. I think a big reason why people are alienated from the word ‘feminism’ is that they’re just not familiar with it.”

With women’s voices being dismissed again, we can’t afford to be polite about feminism. Ms. models how boisterous, unapologetic activism works. The consciousness-raising groups, the taboo-breaking coverage, the willingness to piss people off—that’s the template.

Feminism might be polarizing—but it’s most certainly not outdated. So watch the film, yes. But then ask yourself: What would your version of Ms. magazine look like today? What conversations are we still afraid to have? What taboos are ripe for the breaking?

Because the alternative—staying silent or anxiously scrolling—leaves us invisible and alone. And we’ve tried that already.

******

The documentary Dear Ms.: A Revolution in Print releases July 2, 2025 on HBO Max.