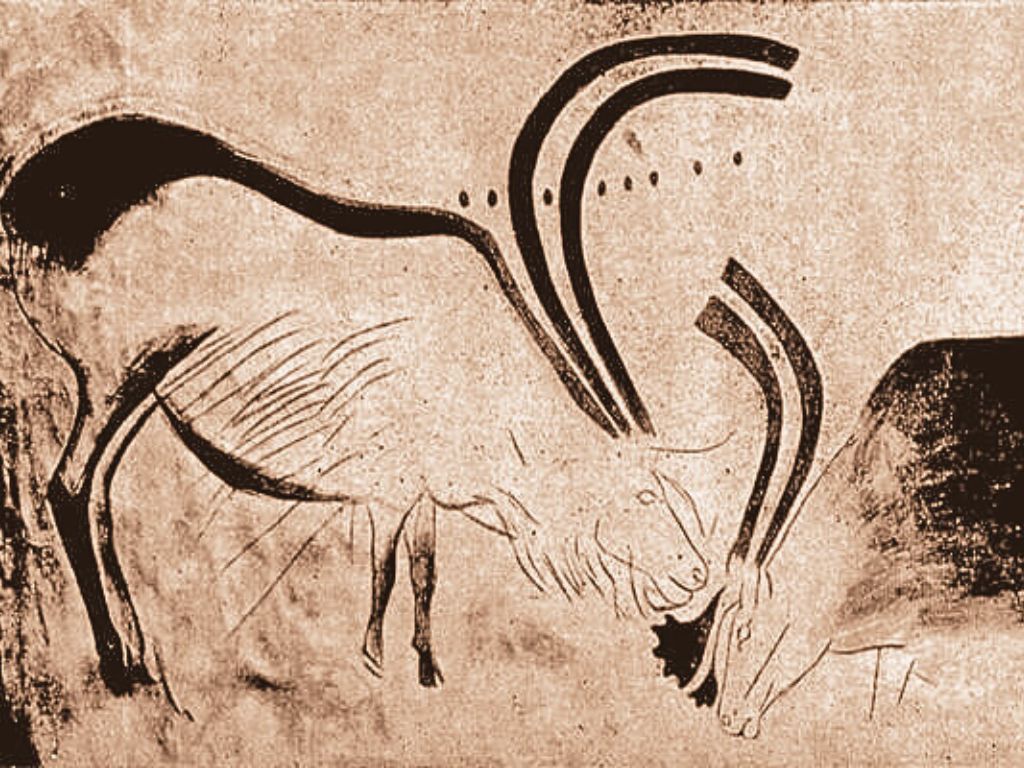

Image: Capitan L., Breuil H., 1903

In the depths of a French cave, 17,000-year-old drawings cracked open something I didn’t know I was missing.

Spiritual is not a word people commonly associate with me. My sister in New York is the one who channels and manifests. I’ve long said the wrong sister moved to California.

No personal God or goddesses for me. No heaven, no hell, no still-communicating spirits of the dead. Don’t get me wrong: I wish there were an afterlife and would love to be pleasantly surprised by a loving, intelligent Higher Being greeting me postmortem to chat about the latest books. (What’s heaven without books?)

But analytical and science-based has always been my style. I can’t even meditate to save my life.

When Logic Breaks Down

The woman who doesn’t do “woo” finds herself moved over a bison in the dark.

And yet last year, at age 70, I found a sense of enlightenment in a literally dark place: The long, tight tunnel of a French cave where I saw the 17,000-year-old drawing of a dappled brown bison and an ochre-tinted leaping horse. Another drawing gracefully outlined the image of a standing male reindeer tenderly licking the forehead of a bowed-down female. They were a few of the hundreds of cave paintings that reordered my view of life and what lives beyond it.

Image: Don Hitchcock 2008

They awed me. Knocked my intellectual curiosity on its logic-reliant butt. I no longer was an information-seeking onlooker, but rather a small yet uplifted creature. The world felt bigger, my breathing lighter and fuller.

The feeling was addictive. I had to go back, and for longer. So this year, I stayed in the same quaint 1700s cottage in the Perigord region, buying produce at the same outdoor village markets, eating the foie gras and crusty baguettes. But this time, I hired an archaeologist who had written a book about the local caves to take me on private tours of them. A repeat visit to Font de Gaume from last year, plus four others.

Caves Don’t Lie

Bear nests and graffiti—all layered in the same limestone theater of time.

In one cave, the image of a female face was notched into the wall, except when viewed from 10 feet over to the right, it looked like Genghis Khan. In another, a Picasso-like abstract drawing of a baby woolly rhino dispelled any idea that this deft cave art is “primitive.” I was dizzied by images of mammoths and other Ice Age beasts surrounding me on all sides and even above my head, each outlined in a single masterful stroke of the drawing implement. Along the way to those hundreds of drawings, I passed dozens of scooped-out “bear nests”—much like the way my dog dug a comfortable depression in the slope above my yard (thus nearly killing a tangelo tree). Cave bears hibernated in this cave, and the nests they dug here have remained undisturbed for at least 27,000 years when the species went extinct. A more modern touch on the walls and ceiling: graffiti dating back as far as the 1600s.

It was that long wave of time that swept me up into something bigger. At gut level, for once not using my brain, I suddenly stopped seeing myself as an independent person with her own world of work, people, and interests. Instead, I saw the speck that I am, woven into the very long story of homo sapiens. These artists could even be my ancestors, though they didn’t pass their abilities on to me.

I stood in the same spot as the people who felt compelled to draw these images—which was no mean feat. If I touched the wall (strictly forbidden!), I would feel the same rock they did. But without my hands, I could still feel them reaching out through their artwork, through the millennia to all who are lucky enough to see and receive at the other end. Which for me, happened to be right at that moment.

Art as Survival, Art as Signal

They weren’t doodling. They were saying something. We just haven’t cracked the code.

But what was I receiving? No one knows the purpose or meaning of cave art. Were they anointing a place they thought of as special, protecting their creativity from the elements, or telling a story? Or were they just making pretty pictures to pass the time?

They obviously weren’t just doodling. It was grueling work to get through narrow, low-ceilinged passages and draw animals in a single stroke on a rough wall, or build scaffolding to reach up 20 feet. It took talent—it’s probably not something that everyone did—and planning to use the contours of the cave walls for their art. A protrusion becomes the shoulder hump of a bison. And in a couple of cases, they signed off, leaving negatives of their own hands by putting them against a wall and blowing powdered coloring around them. At least one of them is clearly that of a woman, our guide told me. “I was here.” Yes, I could sense it.

They weren’t the interior decorators of their homes. “Cavemen” didn’t actually live in caves for the most part. The animals don’t represent the hunt; people mostly ate reindeer, which are rarely on the walls. Instead, there were images of mammoths, bison, horses, aurochs, and occasionally bears. They rarely drew people and almost never showed them as complete figures. What was that all about?

The Godless Get Spiritual Too

You don’t need a personal deity to feel a presence

Standing in the cave, I understood why I’d always been drawn to archaeology—why I swooned over James Michener’s The Source in eighth grade. Why I went back to college part time to become an archaeological technician. Why I’ve volunteer on digs. It’s the same feeling: the ability to unearth and touch the objects created by humans long ago, as though I were somehow touching those people themselves.

The message of the people of Perigord, making their literal mark 17,000 to 27,000 years ago, somehow connects me to a long tunnel of time. It’s as if they were speaking, but from far away and behind glass. I can’t hear them and I’ll never know the message except that they were there, leaving a tangible remnant of their lives that others in the future would see.

Time To Leave My Mark

Seventeen millennia later. Now it’s my turn to reach forward.

Those artists reached across 17,000 years and touched me, whether that was their intention or not. Now it’s my turn. What mark will I make that might reach someone thousands of years from now? What stone will I drop—or maybe have already dropped—in the water? Maybe one day, a faint ripple will greet someone ready to catch it.

A detailed study of the Font de Gaume cave paintings can be found here.

So eloquently written. Definitely feel your awe. I found this very inspiring. Thank you.

Oh Karin, I am so moved by your eloquent essay. Thank you.