Image: SFD Media LLC

The Simple, the Universal, and the Human Need for Meaning

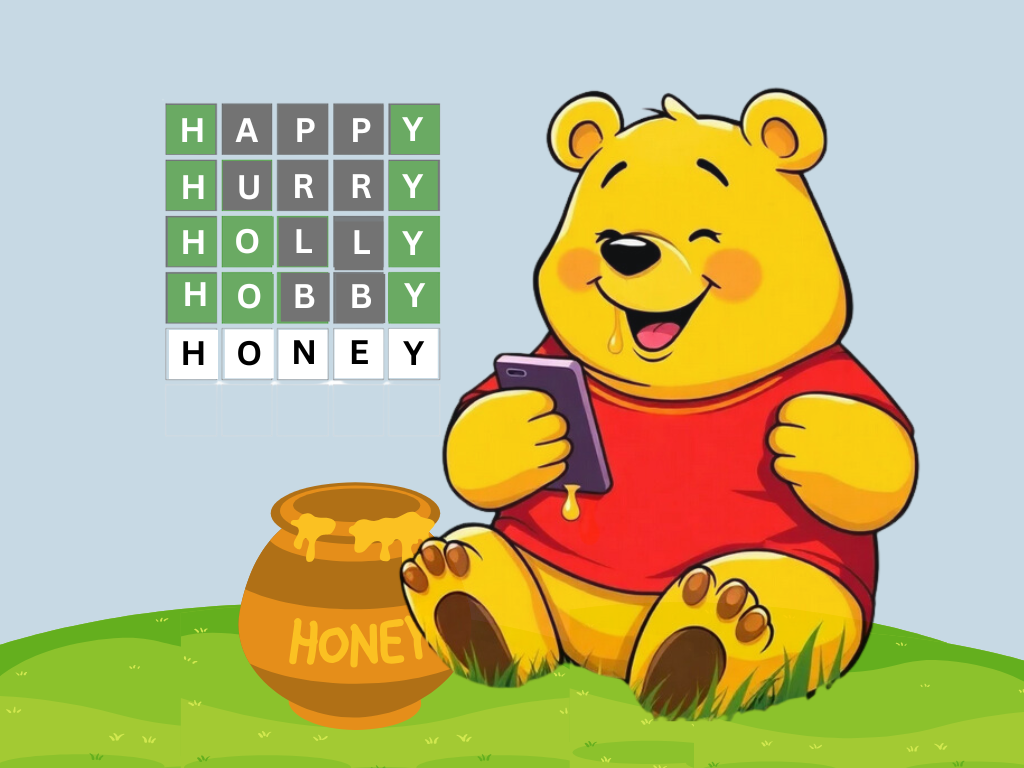

Why do we gravitate toward the simple when life feels overwhelmingly complex? Perhaps it’s because the simple reminds us of what’s essential. Take Winnie the Pooh and Wordle—two cultural phenomena that, at first glance, couldn’t be more different. One is a storybook bear navigating honey pots and friendships; the other, a five-letter word puzzle testing your wits over coffee. Yet, both tap into something profoundly universal: our need for grounding rituals, shared experiences, and the pursuit of small, satisfying wins.

But here’s the twist: Neither of these creations was designed for the kind of virality they’ve achieved. In A.A. Milne’s time, the word “viral” referred strictly to diseases—certainly not a cultural benchmark. Milne wasn’t angling for fame when he wrote Winnie the Pooh. He was crafting stories for his son, pure and simple. And though Josh Wardle, a century later, lived in a world where virality was a known phenomenon, his creation of Wordle wasn’t a bid for mass appeal. It was a love token for his partner, Palak, during the pandemic.

So how did these quiet, heartfelt gestures become global sensations? And in a world where virality now drives so much creative intent, does their origin story hold a mirror to our own need for validation?

A Legacy of Love in Unexpected Places

“Sometimes the smallest things take up the most room in your heart,” Pooh once said. It’s a truth that echoes in both his story and Wordle’s.

In 1926, Milne wrote Winnie the Pooh as an ode to his son’s childhood—stories steeped in love and whimsy, inspired by stuffed animals and quiet moments in the English countryside. Fast forward to 2021, when Wardle created Wordle for Palak as a daily puzzle to bring her joy during lockdown. Neither Milne nor Wardle envisioned their creations reaching beyond their intended audiences, and perhaps that’s why they resonate so deeply.

There’s something refreshing, even radical, about creating for the sake of connection rather than applause. Can we still do that? Or has the pressure to go viral rewired our motives?

Gender Studies and the Patriarchy

How’s that for a clickbait title? No, I’m not actually going to unpack the patriarchy here, though inevitable academic studies do try. Some claim Kanga, the sole female character in Milne’s stories, represents domestic servitude under male hegemony—other’s accuse Owl of mansplaining!

But even if these suggestions feel overblown, they tap into something worth exploring. Both Pooh’s stories and Wordle have a simplicity that resonates deeply with women of a certain age—those of us juggling careers, caregiving, and the incessant demands of everyday life. In these spaces, where meaning is found during quiet moments and rituals reign, we reclaim time for ourselves.

Pooh’s stories unfold with gentle predictability: exploring the Hundred Acre Wood, solving small dilemmas, leaning on friends. Similarly, Wordle offers a steady rhythm: coffee, puzzle, results, repeat. Yet even these rituals, quiet as they are, now carry the weight of sharing.

Is it enough to solve the puzzle, or do we only feel satisfied once we’ve posted the results? For women, who often bear the social labor of connection, this pressure to perform even during our downtime can feel oddly familiar. Does solving Wordle become less about personal enjoyment and more about participating in a digital ritual of validation?

What Women Can Learn From Winnie the Pooh and Wordle About Moving On

Statistically, some studies show that two out of three Wordle players in the U.S. are women, and over a third of U.S. people over age 35 have played it and like it. In a study by YourDictionary, women were slightly better than men at completing the five-letter puzzle. Neither of these stats mean much to me, but what does is the once-a-day feature of the puzzle. Losing does not compel me to mash the “play again” button in a recursive attempt to win just one time before I quit. Rather, it puts us (or at least the three women I asked) in a state of a mindful present, where each day’s puzzle stands on its own and today’s loss will be forgotten tomorrow in the mists of time (although the NYT attempts to appeal to the more competitive among us by reporting our “current streak.”)

In the same way, our friends in the Hundred Acre Wood find closure in each of life’s chapters. Whether dreaming of Heffalumps that never actually steal their honey, or Woozle footprints that turn out to be their own, Pooh and his friends don’t have recurring villains or unresolved ambiguous conflicts. This is exactly the opposite of the frequently male-centric “hero’s journey” in Joseph Campbell’s framing of literature; rather, a small problem turns out to be a non-problem and by the end of the chapter they can move on. Try reading one chapter of Winnie the Pooh or House at Pooh Corner, put down the book, and read another chapter in any order the next day. Yesterday’s problem, like yesterday’s Wordle, doesn’t affect me today.

Virality: From Pure Creation to Performance

Milne and Wardle operated from a place of purpose, not performance. For Milne, there was no concept of “going viral”; the idea that one’s work could ripple across the globe in seconds would have been inconceivable. For Wardle, virality was very much part of the zeitgeist, but he wasn’t chasing it. In fact, the game’s original name—Mr. Bugs’ Wordy Nugz—is proof enough that mass appeal wasn’t on his radar. The goal wasn’t fame but joy. Pure, simple, and specific.

Compare that to today, when virality feels like the holy grail of creative output. How many of us create something with the hope that it “blows up,” that it’s shared, liked, and validated by strangers? And how often does that pressure dilute the authenticity of what we make?

Milne and Wardle remind us that sometimes, the best things are born when we’re not trying to impress anyone. What might you create if no one but one person were meant to see it?

Are Digital Rituals Enough to Keep Us Connected?

What truly binds Winnie the Pooh and Wordle is their ability to connect us. Pooh’s adventures are grounded in friendship and community, while Wordle creates its own kind of digital following. Families debate strategies, coworkers share scores, and strangers bond over shared triumphs.

But let’s push this further: Are these small moments of connection enough? Or have they become placeholders for deeper, more meaningful relationships? My son and I exchange Wordle strategies (his opener: RAISE, mine: SLATE), just one of the many ways we connect—but it makes me wonder: How often do we let small rituals like this carry the weight of deeper connections?

And then there’s the social pressure of connection. Sure, most of us are content to share our scores with friends or family, but imagine trying to crack Wordle in Matt Damon’s group chat. It’s said that Ben Affleck couldn’t cut it under Damon’s high-stakes Wordle rules. Can we talk about how even a friendly puzzle can morph into a competitive blood sport? “Oh bother,” indeed.

Simplicity is Timeless: From Winnie the Pooh’s Wisdom to Wordle’s Charm

Socrates and Confucius alike praised simplicity as the path to wisdom. Pooh and Wordle are modern echoes of that wisdom, stripping life down to its essentials: connection, presence, and joy. But in our rush to complicate, monetize, and share everything, have we lost the ability to embrace the quiet and unadorned?

Both Pooh and Wordle started as small, unassuming creations and became larger than life. Milne’s bedtime stories morphed into a Disney empire. Wordle, a private love letter, became a New York Times acquisition. But with that growth comes a question: When something created for one becomes consumed by millions, does it lose some of its magic?

At their core, Pooh and Wordle show us that meaning doesn’t have to be grand. It can be as small as a bear searching for honey or a green square lighting up your screen. They remind us that the profound often hides in the humble—and that the joy of creation, connection, and ritual can endure beyond trends.

But here’s the real question: Are we ready to stop chasing virality long enough to notice?

Do you have daily rituals that ground you? Or has the constant demand for productivity and performance erased them? And when was the last time you let something small and simple be enough?

0 Comments